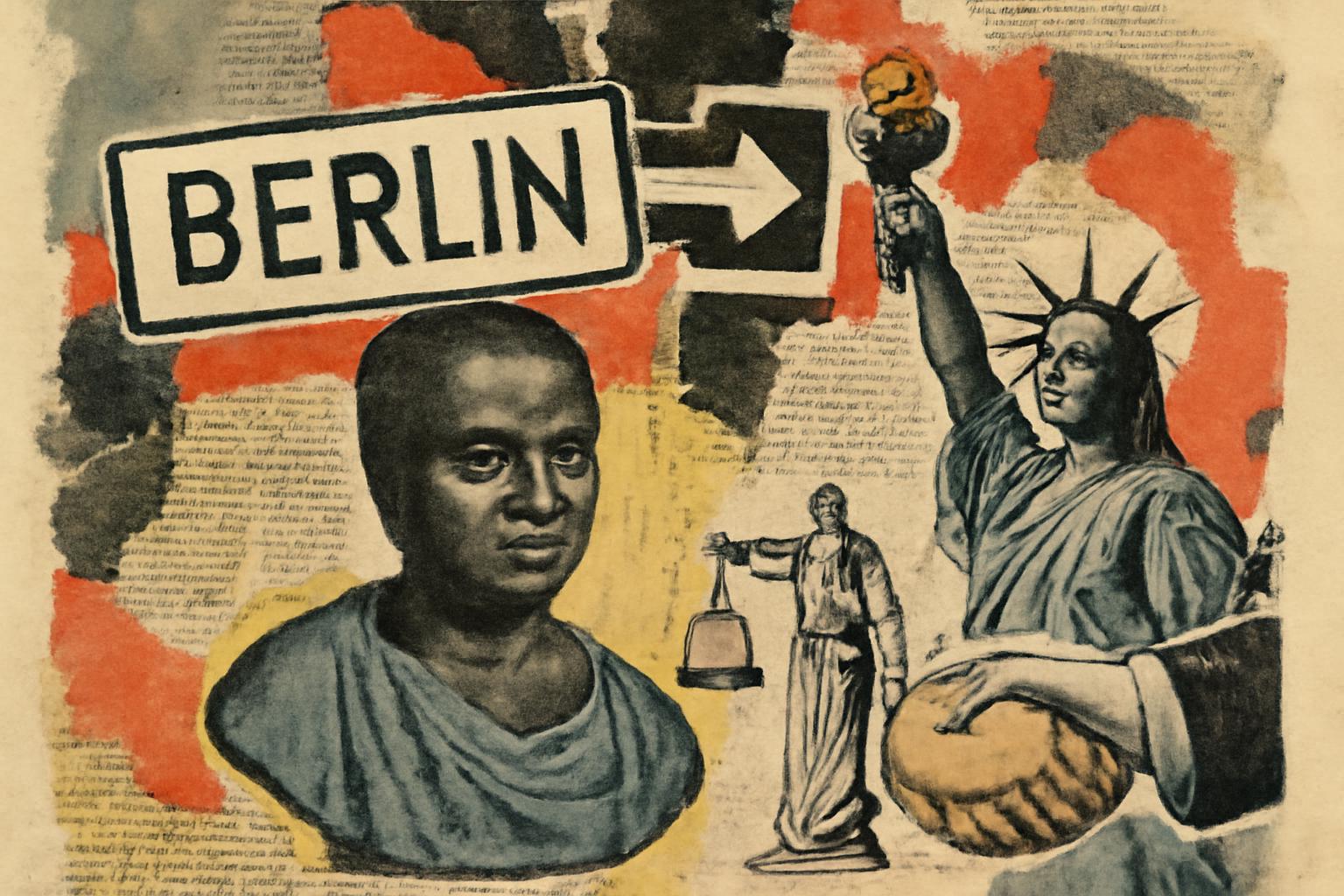

A Berlin street has been renamed to Anton-Wilhelm-Amo-Straße after a court cleared the district to proceed, with a celebratory festival near Hausvogteiplatz and a lineup of groups arguing that the change reflects a broader shift in public memory. The ruling came shortly after an urgent injunction by a citizens’ initiative and amid political back-and-forth: Green Party lawmakers welcomed removing a term deemed racist, while the CDU argued residents weren’t sufficiently consulted. The process highlights a public-asset decision made by the state, touching institutions from the Federal Ministry of Justice to Humboldt University’s Institute for European Ethnology. Anton Wilhelm Amo, cited as the first Afro-German academic, is presented as a historical figure worthy of commemoration; Amo’s trajectory—from enslaved child to philosopher in Halle and Jena—frames the change as a corrective to a painful past embedded in the city’s geography.

From a libertarian vantage, this is a stark example of state power stepping into a moral-cultural arena where dispersed individual knowledge and choices should matter more than centralized orchestration.

Hayek would warn that centralized social engineering of memory invites miscalculation and limits the spontaneous order of local preferences. The city’s decision to rename a public street uses coercive machinery funded by taxpayers and imposes a particular narrative across a shared public space. The deeper lesson is that memory, history, and tribute emerge best from diverse, voluntary actions within civil society, not from top-down mandates backed by the monopoly on force. The rule of law should shield individuals from arbitrary coercion, not become a tool for “corrective” social engineering that preempts plural debate.

Nozick would ask whether this renaming respects individual rights and property in the broad sense of voluntary consent and nonaggression. If the change represents a consensual evolution of public space through legitimate institutional processes that respect dissent and do not coerce non-consenting owners or residents, it might be tolerated within a minimal state’s protective remit. But if the process suppresses minority views, imposes a preferred ideology, or diverts resources away from rights-protecting functions (like policing, contracts, or defense) to symbolic redress, it risks violating the entitlement framework. In Nozick’s terms, the legitimacy of such a move hinges on respect for voluntary agreement rather than moral grandstanding.

Rand would bluntly oppose turning public space into a moral theater for collectivist ethics. She would call out the move as a collectivist effort to legislate virtue and rewrite memory through state-backed sanction. The only legitimate end for government, in her view, is the protection of individual rights—against force, fraud, and coercive redistribution—not the imposition of a preferred historical narrative. She would insist on protecting dissenters’ rights and encouraging private, voluntary commemoration rather than state-enforced symbolism. If the scene feels like coercive consensus built on power rather than principle, it runs counter to individual rights and rational self-interest.

What this really exposes is the tension between a state that uses coercion to shape memory and a libertarian conviction that memory and tribute should arise from voluntary, diverse, noncoercive action. If we are serious about honoring figures like Amo, the correct move is not to city-script a memorial through celebrated court rulings and public-signage mandates, but to let civil society—private foundations, donor-supported museums, scholarly programs, and voluntary associations—sponsor exhibitions, educate, publish, and contextualize. Let communities volunteer to rename, fund, or create alternate commemorations; let private streets, signs, and information boards reflect a plurality of histories. And above all, keep the state out of the business of policing memory. The only lasting tribute to liberty is a public sphere where ideas compete, consent is prized, and coercive power is restrained.