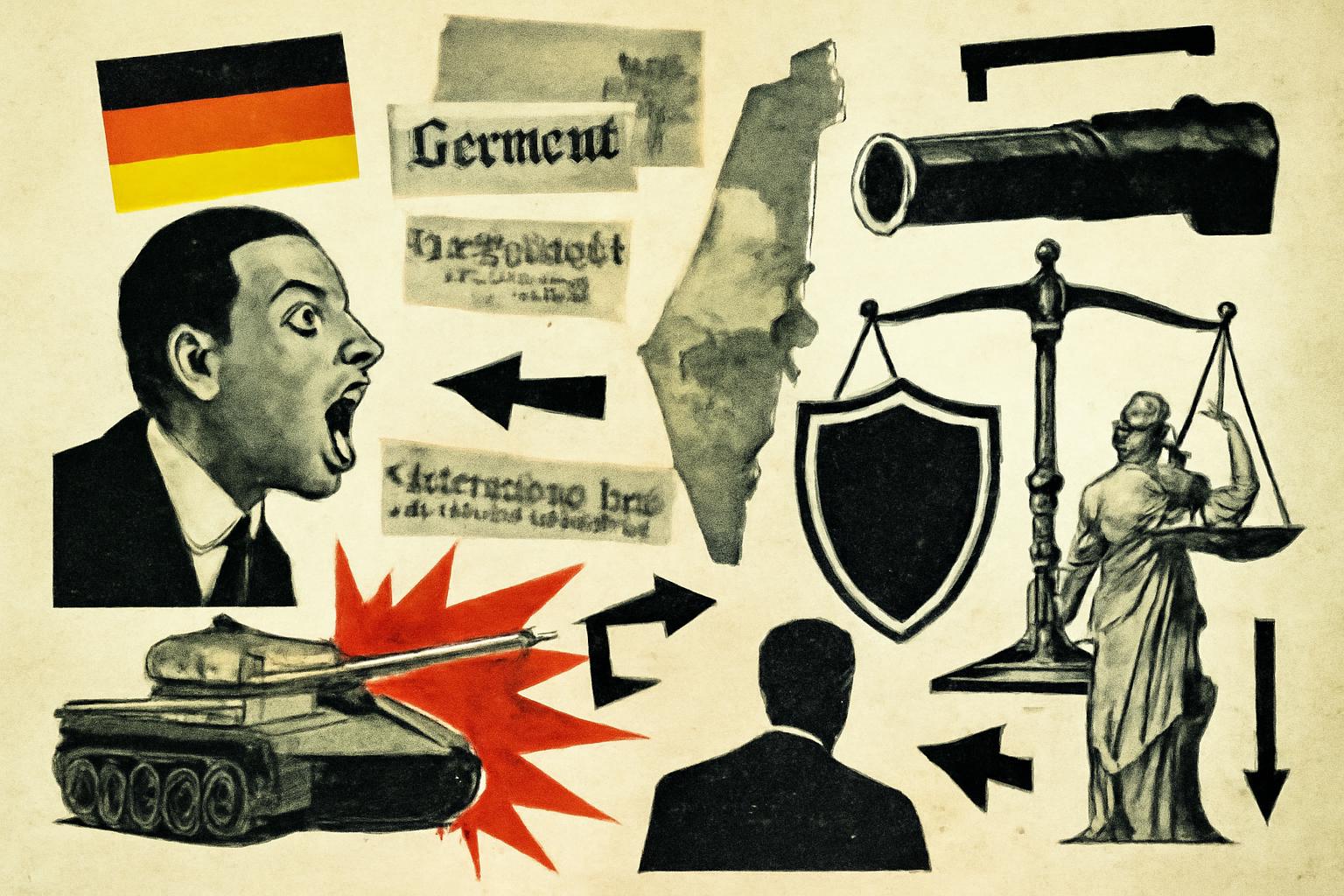

Germany’s pause on arms exports to Gaza has ignited a debate about staatsräson—whether Germany must act as a historically responsible actor in the world or whether it should resist being pulled into moral scripts about universal rights and humanitarian duties. Merz says there’s no rupture in core policy, while CSU voices warn of fracture. Some scholars call the move a necessary recalibration, others see it as signaling a new stance toward Israel. Berlin grumbles that promises of more aid haven’t shown up as action, and a think tankian frame sees this as restoring balance between historical responsibility and universal rights, not tearing down a strategic relationship. In short, the debate centers on whether a state acts at all as a moral agent in foreign affairs or simply as a coercive allocator of resources—whether it should intervene to shape outcomes or leave the matter to voluntary exchange and reciprocal defense.

From a Hayekian angle, the impulse to rewrite or recalibrate arms policy midstream is a blunt reminder of the knowledge problem that plagues centralized moral budgeting. Central planners presume they can weigh “principles” and outcomes with perfect foresight. But markets, communications, and national-security realities are a complex, dispersed order. When the state asserts it will recalibrate arms exports to satisfy a moral or legal imperative, it substitutes platitudes for information and creates distortions in price signals, risk assessments, and supplier-consumer expectations. It invites coercive tinkering with the delicate web of private actors—firms, insurers, buyers, and allied governments—whose plans and property rights are the actual sediment of peace and prosperity. The proper response, Hayek would argue, is to minimize state intervention in such trades and to rely on the rule of law to protect life and property, not to micromanage exports in the name of “historic responsibility” or “universal rights.”

Nozick would push the argument further toward the boundary where coercion ends and voluntary exchange begins. Foreign policy, for him, is legitimate only insofar as it protects individual rights and does not confiscate wealth or compel people to fund actions they disapprove of. The state’s power to tax citizens to fund arms exports, to license or pause sales, or to impose moral conditions on allies is a classic rights violation when it overrides consent and property rights. The idea that a state must enforce a broad set of duties—historical responsibility, universality of rights, humanitarian law—at the expense of private contractual relations and peaceful trade is precisely the kind of coercive redistribution Nozick criticizes. Alliances and aid become forms of coercive solidarity unless they are supported by voluntary agreement, not by bureaucratic fiat.

Rand would bring the discussion to the moral core of rational self-interest and the primacy of individual rights. A true defense of life and property does not hinge on sentimental appeals to “our historic duty” or “universal rights” if those appeals justify coercion or enable moralistic meddling that harms peaceful people. If arms trade is a legitimate private transaction between consenting parties under a framework of clear property rights and rule of law, Rand would defend it as an extension of voluntary exchange and individual responsibility. But she would reject any policy that treats others as a means to a political end or that justifies state coercion in the name of abstract obligations to distant populations. A Randian libertarian would insist that the state’s job isn’t to arbitrate moral grand narratives but to protect rights and to stop itself from funding policies that escalate violence or entangle otherwise peaceful individuals in coercive schemes.

So what does this mean for the German moment? It signals the dogma masquerading as statecraft—the attempt to balance “two pillars” of historical responsibility and universal rights—versus the libertarian insistence that the only legitimate end of political power is the protection of individual rights. The appropriate libertarian stance would be:

- Shrink the state’s reach in foreign arms policy to preserve rights and property, not to impose moral litmus tests on moral actors. Stop treating export licenses as instruments of moral pedagogy or geopolitical scriptwriting.

- Treat alliances and defense as voluntary, not as obligations funded by coercive taxation. If private firms and private buyers can transact with transparent risk disclosure and mutual consent, let those exchanges occur rather than be filtered through a political gateway.

- Reject the notion that a nation’s “universal rights” duty justifies coercive redistribution or strategic interference with potential arms sales. The right metric is rights-respecting civil order at home and freedom from the state’s moralizing meddling abroad.

- Favor a Hayekian liberty of exchange: disaggregate knowledge, trust prices and incentives, and let a decentralized system allocate resources. Central policy “rebalancing” on moral grounds introduces distortions that ripple through security, trade, and private property.

- Apply a Nozickean lens to humanitarian rhetoric: if the policy requires coercion, redistribution, or forced alignment with distant moral regimes, resist it. The legitimate foreign-policy act is the protection of rights, not the enactment of moral vanity or strategic signaling.

In practical terms, a libertarian reading would advocate ending or at minimum severely narrowing state-directed calibrations of arms exports, refraining from using foreign policy as a vehicle for grand moral choreography, and instead letting private actors, with clear rights protection, determine who buys what and under what risk framework. The state should be a shield for individuals’ lives and property, not a loom for weaving national mythologies about responsibility or universalism. If Israel’s security is a genuine concern, the answer lies not in mandating or approving every action of a government but in respecting the rights of all affected parties, avoiding coercive subsidies or restrictions, and allowing peaceable, voluntary exchanges to define security and prosperity.