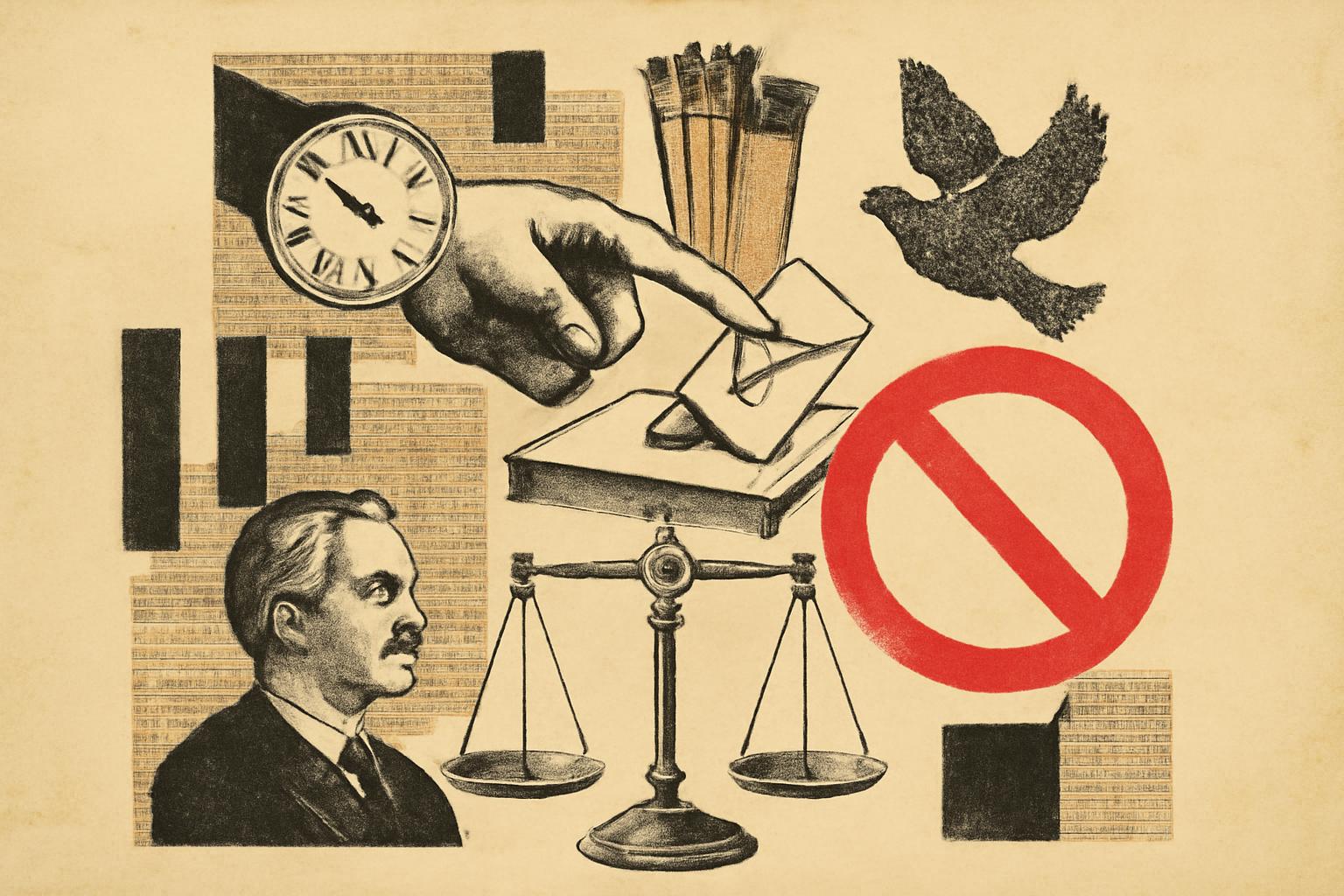

A plan circulating would extend the Bundestag term to five years and bundle elections so that Bundestag, municipal, and state elections would largely occur on coordinated days, with constitutional changes needed to make that legally possible. The practical hurdles are immense: cross-state coordination, the Basic Law’s four-year Bundestag term, and state constitutions—requiring a two-thirds majority in both the Bundestag and the Bundesrat.

From a libertarian vantage point, this is the state attempting to engineer the very rhythms of political life in the name of “efficiency.” Hayek would warn that such bundling pretends to knowledge the central planners do not possess. The decision when and how people vote is a form of dispersed information that best resolves itself through voluntary, decentralized processes. Centralized timing concentrates political power, slows accountability, and creates incentives for longer-term policy drift under the illusion of orderly, planned governance. The longer the term and the more rigid the election calendar, the easier it is for governments to pursue agendas with less frequent public scrutiny and fewer immediate consequences for missteps.

Nozick would argue that the coercive apparatus of the state—taxation, law, and the legitimization of power—already runs the show enough. Lengthening terms and tying elections together compounds that coercion by making it harder for citizens to change course in response to poor governance. The BundStat’s scheduling becomes another mechanism by which the state sustains itself rather than a neutral referee among rival political claims. If the aim is to minimize coercive power and maximize individual freedom, the default should be less centralized control over political life, not more.

Rand would urge you to see this as a surrender to collectivist rationales that treat citizens as fungible units to be managed rather than individuals with inalienable rights. The ends—“stability,” “efficiency,” or “policy implementation”—do not justify the means of altering constitutional structures and election calendars. A government that uses constitutional amendments to entrench longer terms and synchronized elections is exerting power not to protect rights, but to reduce accountability and entrench itself.

Libertarian paths forward would emphasize maximal accountability, minimal necessary coercion, and competitive governance rather than centralized timekeeping of elections. Shorter terms, robust term limits for executives, and even more pronounced decentralization would allow citizens to exit bad governance quickly and to migrate to jurisdictions with policies they prefer. Constitutional changes should be rejected unless they enhance individual rights and reduce state power. If one truly seeks “stability,” the answer is not longer terms and fewer elections, but a freer system where laws are clear, propertied rights are protected, and political power remains as close to the people as possible, with the rule of law that Hayek championed as the safeguard against the tyranny of centralized planning; a system where Nozick’s minimal state is kept in check by vigilant respect for individual sovereignty; and where Rand’s insistence on rational self-interest and strict anti-collectivism keeps the state from claiming a mandate it has no right to wield.