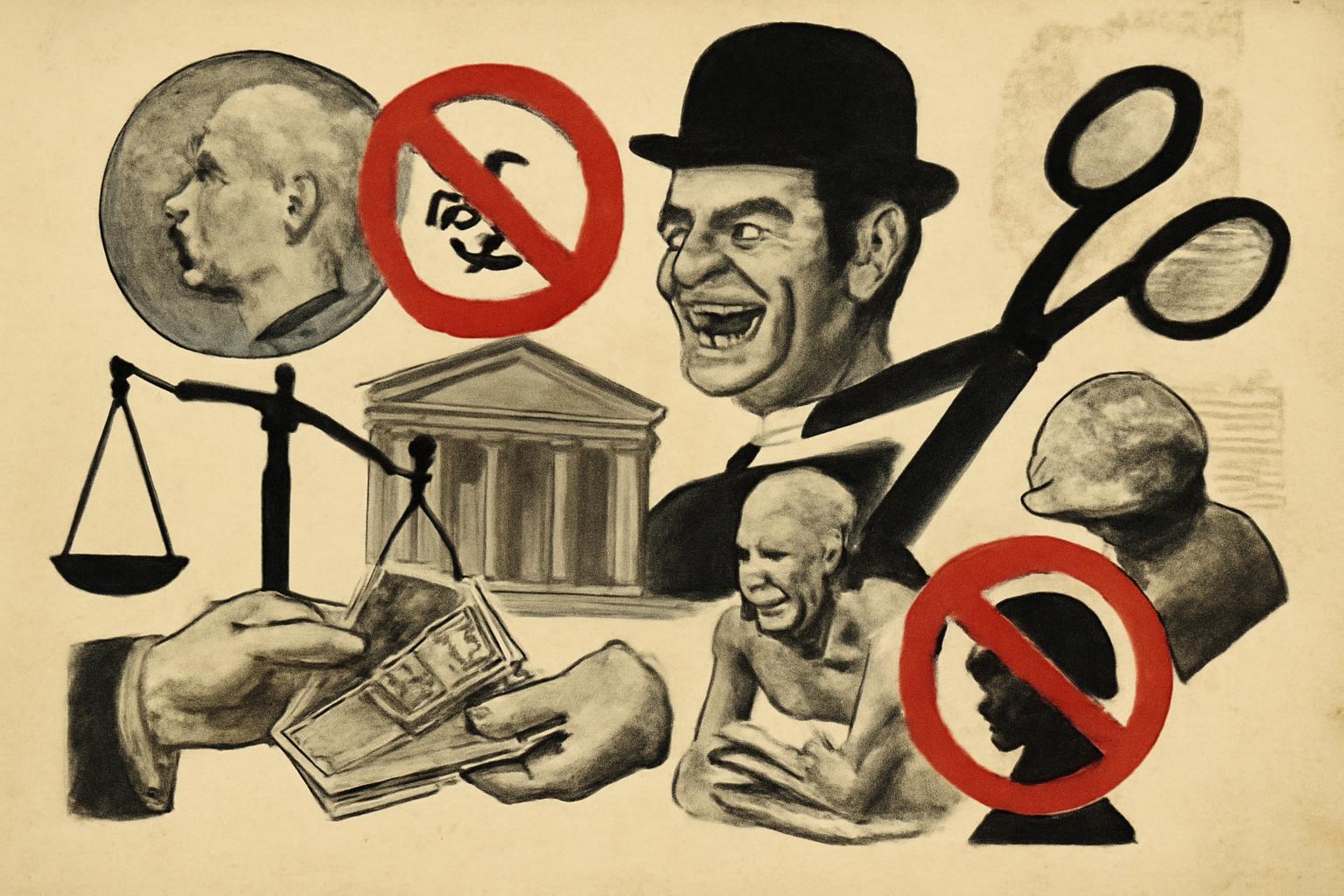

Söder wants to tinker with tax and welfare from the top down, patching the system with regional experiments while pledging not to raise overall taxes. He talks of regional inheritance tax levels, a supposed “switch” to let Länder set rates, and he rules out broad tax hikes. He rejects a wealth tax as legally and practically problematic yet treats the state as the dispenser of favors and rules at the same time. He backs reform of the Bürgergeld and a modernized welfare state to curb abuse, while keeping the pension system essentially intact but adding new options for the young, capital-backed components, and a Frühstartrente—all under a government that still claims to deliver while blaming missteps on others. He drapes these moves in national cohesion rhetoric, but the underlying logic is the same: more state control, smarter targeting, more dependence on bureaucratic management.

From a libertarian vantage point, this is the creeping logic of centralized power dressed as prudence. Hayek would remind us that the knowledge necessary to fine‑tune tax rates, welfare eligibility, and pension incentives lives in countless hands, not in a single room of political genius. regionalizing inheritance tax is, in effect, a new layer of coercive rent-seeking under the banner of “local efficiency.” The market’s spontaneous order and the price signals of private property rights get distorted whenever the state decides what you may do with what you inherit, even if one region pretends to be gentler than another. Nozick would call this a direct infringement on individual rights: taxation as a coercive transfer from person to state, not voluntary exchange or earned entitlement. The more you carve out exceptions and regional variances, the more you institutionalize coercion with a smile.

Regional wealth taxes and a bazaar of habeas-corpus-like welfare controls aren’t just legal fictions; they relocate coercion. Rand would insist that individuals have a right to the fruits of their own labor and capital, and that government redistribution treats people as means to a collective end rather than ends in themselves. A wealth tax or an expanded Bürgergeld is a moral compromise with the principle of individual rights, wrapped in the rhetoric of social stability. Libertarians should oppose any expansion beyond the minimal state’s proper function—protecting life, liberty, and property—because every new program creates new ways for politicians to control, bureaucrats to mismanage, and citizens to subsidize others’ choices at gunpoint.

On pensions and social insurance, Söder’s openness to capital-backed components and Frühstartrente signals a shift toward privatization by design, but it remains a state-backed scaffold. The correct libertarian move is clear: retire from the pawnshop of public pensions altogether and unleash private saving, voluntary retirement markets, and individual responsibility. Hayek warned that central planners cannot foresee all consequences of centralized schemes; Nozick would emphasize that individuals should own and control their own futures, not be tethered to a state-controlled “security” program that can be expanded, pruned, reshaped, and taxed at whim. Rand would add that the moral purpose of finance is voluntary association and personal initiative, not compelled redistribution or bureaucratic guarantees.

Conscription as a quick fix to strengthen the armed forces is the quintessential coercive instrument. A libertarian response is categorical: no forced service. No matter the urgency, conscription violates individual rights and turns defenders into state property for a time. A real defense requires disciplined, voluntary service, redirected to a peaceful, competitive security sector where private contractors and civil-society resilience complement national defense. The state’s claim to strengthen the military by compulsion is the very opposite of the free society Rand champions and Nozick defends. If deterrence is needed, it must come from voluntary, principled security rather than universal coercion.

Foreign policy moves—unity with European partners on Ukraine, caution about large-scale deployments, skepticism about arms deliveries, and hesitation around unilateral sanctions or recognizing a Palestinian state—fit the non‑interventionist impulse. Yet even here the libertarian core questions the premise that the state should police every international outcome. Hayek cautions against top-down moralizing in foreign affairs that inevitably spills into coercive measures elsewhere. Nozick would insist that any action abroad must respect rights and not become a vehicle for redistributing risk or wealth through coercive means. Rand would insist on defending rights without exporting moralism or coercion. Aid should be voluntary and private, not a tax-funded instrument with geopolitical strings attached. Sanctions that punish civilians or unilateral recognitions that redraw property rights illegitimately are not legitimate tools of a free society.

Israel and Palestine present the same libertarian tension: defend the right of a state to defend itself, avoid coercive sanctions that hurt civilians, oppose unilateral recognitions that trample property rights, and favor humanitarian relief through private charity rather than state treasuries. The emphasis on humanitarian aid to Gaza is correct in spirit, but the mechanism should be voluntary assistance, not state coercion or redistribution under the banner of foreign policy. Arms deliveries must be weighed against the same right-to-defense calculus—no moral license for intervention that violates individual rights or creates new cycles of coercion.

In the end, Söder’s program is a case study in the seductive pull of more government power, even when framed as reform. If we take Hayek, Nozick, and Rand seriously, the answer is not cleverer management of a larger state but a drastic rollback to a framework that protects property, enforces contracts, and preserves individual liberty. End the inheritance tax, abolish wealth taxes, shrink the welfare state to its constitutional minimum, privatize retirement security, reject conscription, and govern abroad only to defend rights and enforce voluntary exchange. Let private charity and market mechanisms absorb risk. The state’s proper function is to protect rights, not to engineer social outcomes.