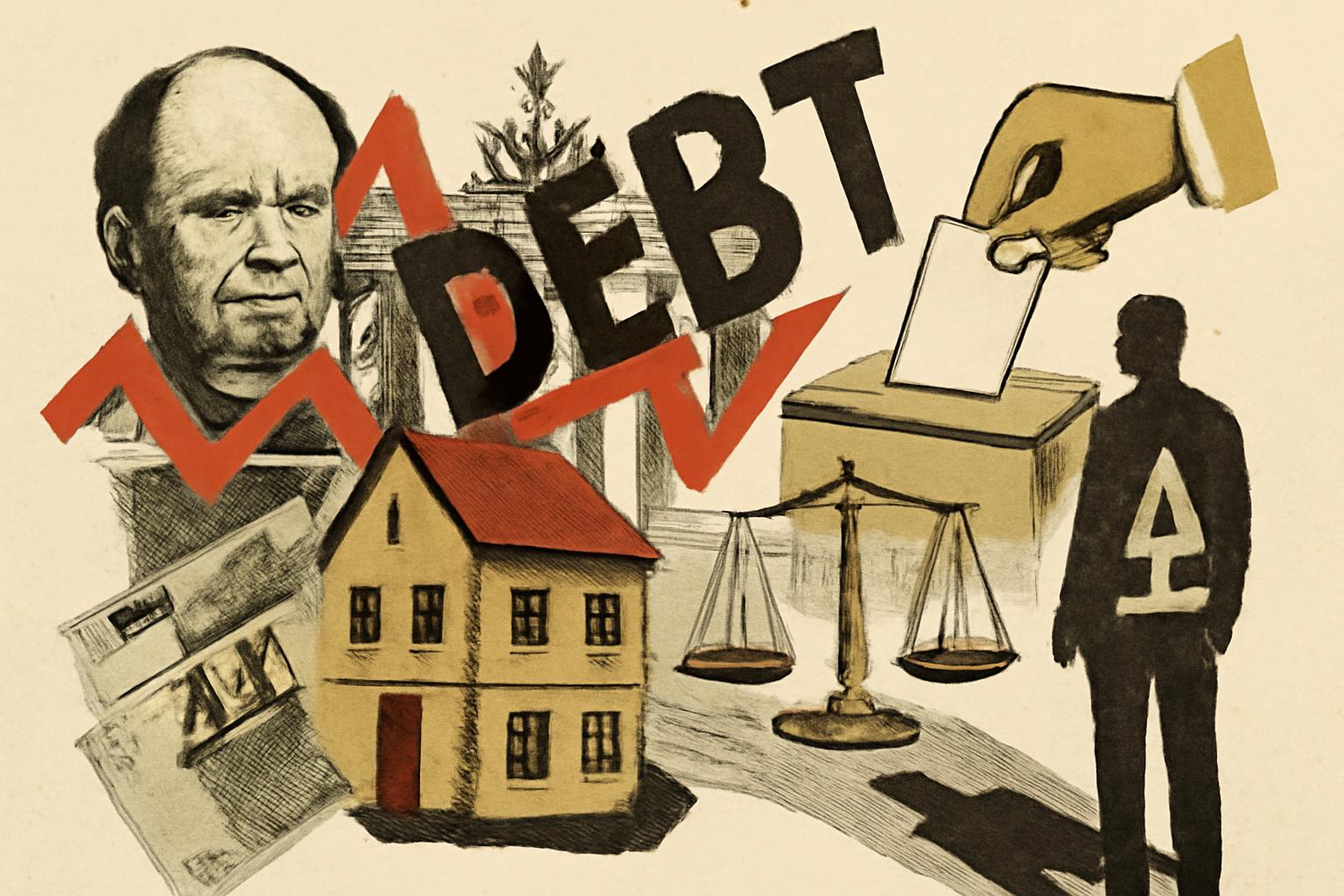

Voters are looking for local results, and the national theater is proving costly to the people who actually live here. After 100 days, the mood is ambivalent at best: debt, Berlin’s backing, and promised gains all become talking points on the street, while Bochum’s residents weigh whether higher-level promises will ever translate into calmer rents, steadier jobs, and affordable housing. Local candidates emphasize on-the-ground cooperation, yet the dynamic remains crowded by federal disputes and the perception that the money tap from Berlin shapes what can be done locally. The sunscreen gag from the CDU’s outreach is a reminder that political theater is alive even where people are worried about real budgets and real consequences.

From a libertarian vantage, this is exactly the kind of situation where centralized direction and debt-financed promises distort incentives and dilute accountability. Hayek would remind us that knowledge is dispersed and that the closer the decision-maker is to the specific problem, the better the remedy tends to be—yet central funding and mandates pull decision-making upward, away from the local realities that matter for housing supply, wages, and municipal services. When debt accumulates to placate voters and Berlin-backed programs glimmer on the ballot, the result is not efficient problem-solving but a hidden tax on future residents and a transfer of risk from politicians to taxpayers who didn’t consent to bear it. The “positive balance” boast is hollow if it rests on commitments not kept or on sources of funds that undermine true accountability.

Nozick’s framework sharpens the critique: taxation to fund ongoing deficits and to prop up central programs is coercive, and the minimum state is supposed to protect rights rather than engineer outcomes. If the money for Bochum’s needs is effectively commandeered from taxpayers, the local community loses a clear line of responsibility—policymakers can dodge accountability by pointing to Berlin’s largesse or to national compromises. A libertarian response is not nihilistic about public goods, but it insists on protecting property rights, voluntary exchange, and local sovereignty over coercive redistribution. When you mix debt, promises, and central bailouts, you transpose the problem from a local budget into a political philosophy: who owns the consequences of those choices?

Rand would push further on the moral and practical grounds: the state’s “solutions” should never substitute for rational self-interest and voluntary cooperation. If rents rise and unemployment worries persist, the cure is not more paternalistic controls or grandiose promises but a freer market for housing, labor, and services, with fewer barriers to entry and fewer omnipresent subsidies distorting prices. The spectacle of campaigns that hinge on federal aid or on symbolic gestures (like sunscreen for political digs) distracts from the moral necessity of letting individuals pursue their own plans under objective law. The proper role of government, Rand would argue, is to protect rights, not to design outcomes or to micromanage local economies with debt-funded programs.

Concrete libertarian prescriptions for Bochum and similar towns: - Slash centralized interventions and subsidies that blur accountability. Let municipalities balance their books and decide locally how to allocate scarce resources without a steady flow of Berlin money propping up politically convenient programs. - Deregulate housing and remove distortions that suppress supply. Permit more private construction, reduce zoning hurdles, and curb rent controls that punish new supply and hurt long-term tenants who need real options. - Decouple public services from debt-financed promises. Limit or sunset mandates that funnel money from taxpayers to politically favored programs; require genuine local consent and transparent budgeting. - Privatize or competitively privatize nonessential municipal services where feasible. Realize better outcomes through competition, user choice, and private management rather than central planning through the purse strings. - Strengthen property rights and the rule of law as the core function of government. Ensure police, courts, and contract enforcement are reliable and predictable, while shrinking the scope of government to protective ends rather than redistributive ambitions. - Encourage voluntary associations and private philanthropy to address social needs, not bureaucratic guarantees from a central government that claims it can “solve” complex problems.

If voters want real change, they should reward candidates who commit to principled limits on state power, robust protection of property rights, and genuine local autonomy over budgets and services, rather than those who promise more Berlin backing or grandiose national resets. The Ruhr region’s future will be determined not by central promises but by the degree to which local actors can operate within a framework that respects rights, prices, and voluntary cooperation—the Hayekian path to a spontaneous order that actually serves the people who live in Bochum.