Under the pallid glare of modernity, the city becomes a stage where order and accident play dice with the fate of the republic. In June, the National Guard descended upon Los Angeles, a solemn implement of statecraft set to quell protests against the immigration authorities, as if a city’s breath could be pacified by marching feet and the rhetoric of security. A California court then drew a line in the sand: the troops may not perform police duties—no arrests, no searches, no seizures, no security patrols, no traffic stops, no seizure of evidence—lest the guardians of the gate turn warders of the street. Yet the judgment did not resolve whether the Guard may remain; it admitted only that there was no rebellion, that civilian law enforcement could respond, and thus the fate of occupation rested in the crucible of appeal. The decision takes effect on the following Friday afternoon, granting the wind a week’s delay for the petitioning eagle to fly or falter.

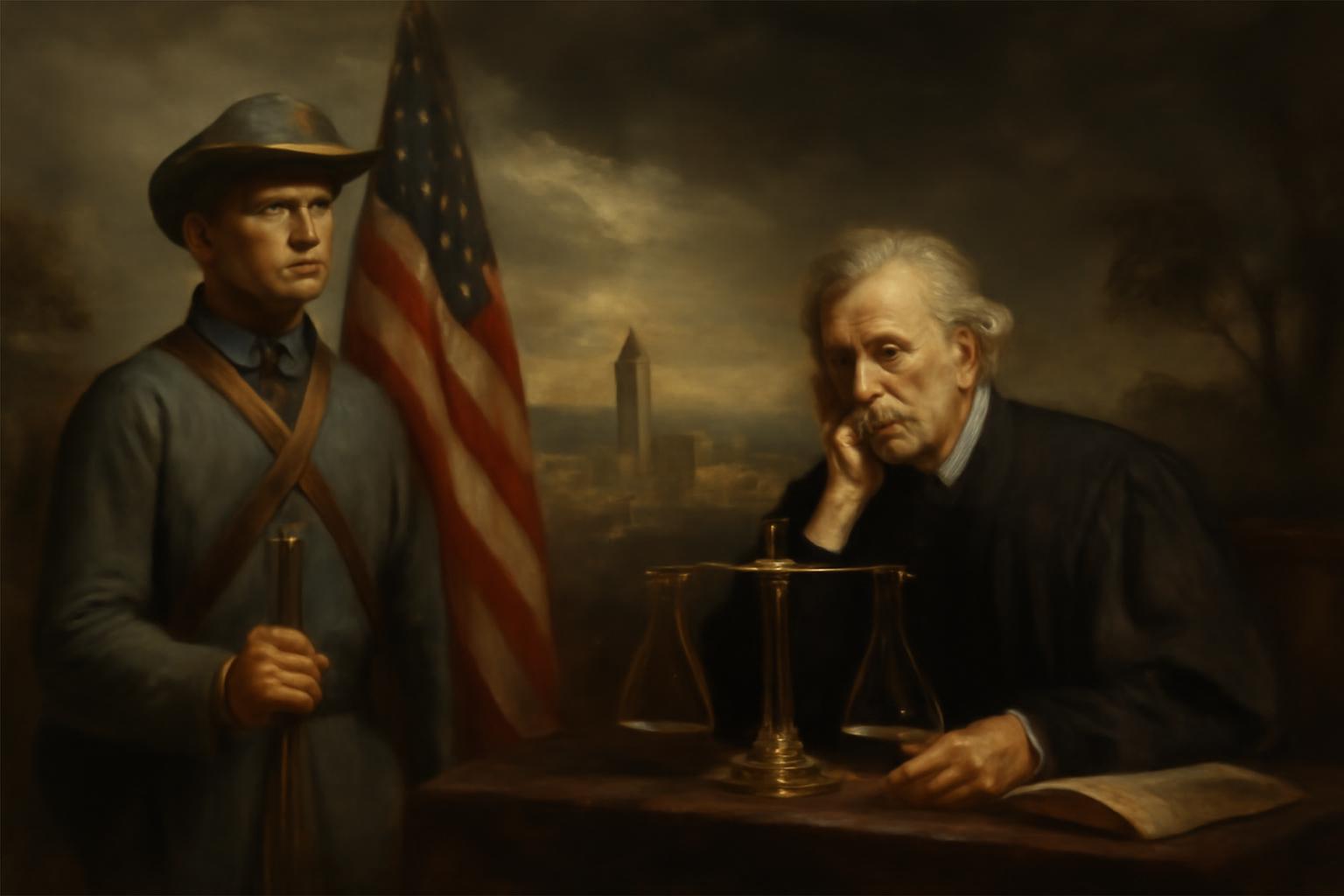

At the heart of the matter lies the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, an antique tether that binds the military from civil law enforcement save for shielding federal facilities, a relic that seems to speak of a civilization aware of its own limits and its own temptations. The legal shell shivers beneath the weight of politics: ongoing tensions between a president and a governor, a rift that leaks into the streets as rhetoric becomes governance and governance becomes theater. Later reports whisper of withdrawal—about 700 Marines and most Guardsmen gone, leaving roughly 300 of the 4,000 still in Los Angeles—a sparing, perhaps, of the sword’s edge.

In the wider republic, governance of the National Guard ordinarily rests with the governors, though the president may seize command in wartime or national emergencies; the Guard remains a reserve for natural disasters, unrest, or internal upheaval, a paradox of power meant to be restrained, not unleashed. Democrats critique the president’s approach, while Chicago is named as another potential stage for deployment, another act in a marathon of statecraft that pretends to civil peace.

Nietzsche would murmur that the will to power masquerades as order, while the Greeks teach that hubris invites nemesis; and so we watch, with a weary chorus, the drama wherein a modern polity tries to keep its own flame alive by calling the flame a badge of security. The decline is not in the fear that drives men to the barricades, but in the creed that calls such fear prudent governance; a civilization that cannot endure the cold glare of its own contradictions, yet pretends that warmth lies just beyond the next decree.