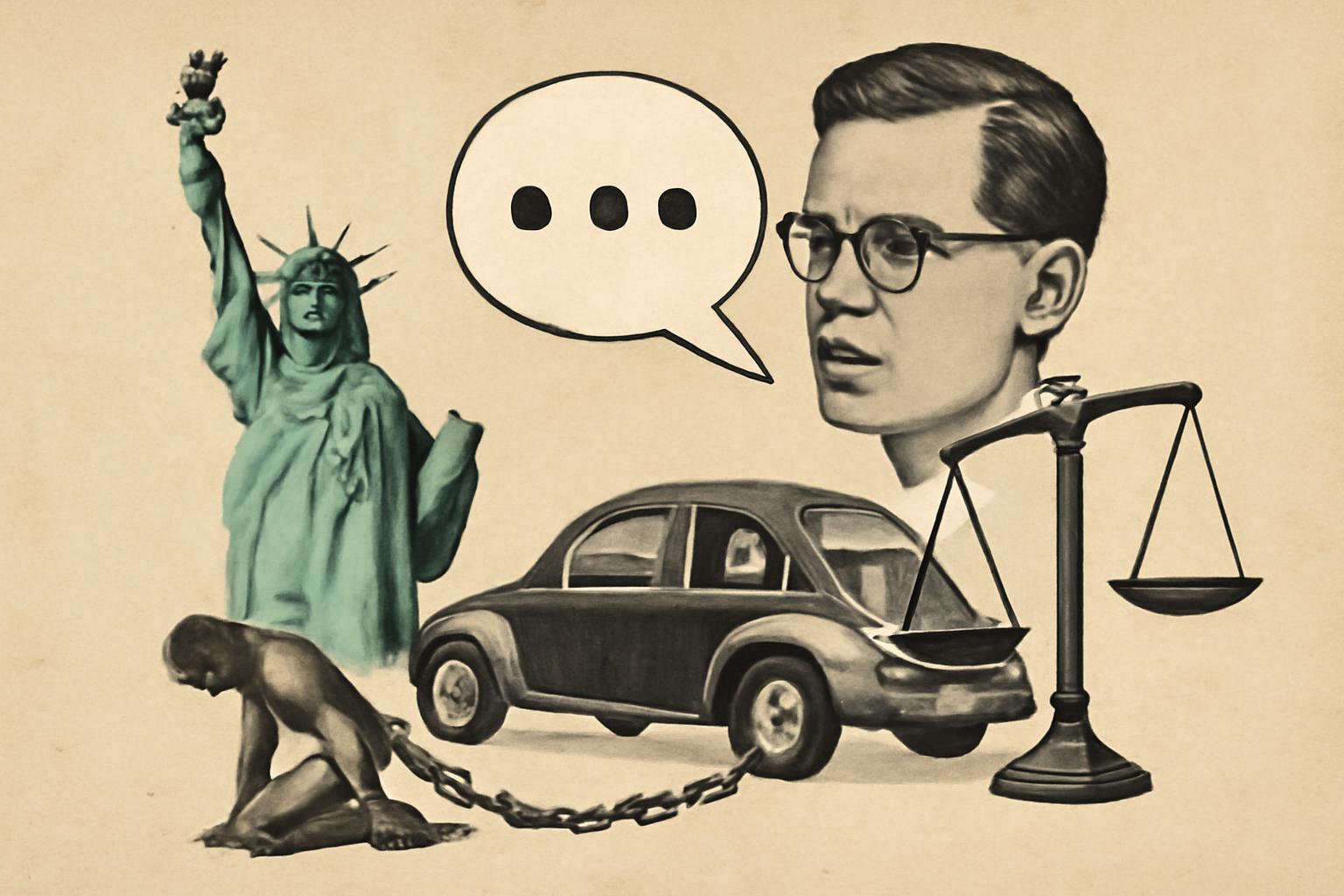

A Brazilian labor court ordered VW Brasil to pay 165 million reais in damages for conditions described as slave-labor–like on a VW‑owned farm in the Amazon during the 1970s and 1980s, and it also requires the company to publicly acknowledge responsibility and apologize to the workers and to Brazilian society. VW plans to appeal. The case rests on documents gathered by Padre Ricardo Rezende Figueira of the Land Pastoral Commission and alleges deforestation, violations of labor law, debt bondage, and armed guards, with claims of murder and torture, underage labor, and encroachment on indigenous lands. One former worker testified to brutal conditions in 1983, with long hours, pay theft, and violent intimidation. The verdict stands as the highest penalty in Brazil to date for modern slavery.

From a libertarian vantage, this case raises fundamental questions about the proper scope and method of addressing egregious rights violations within a voluntary-order economy.

Hayekian frame (rule of law, dispersed knowledge, minimal state) The rule of law should protect individual rights under general, abstract rules applied evenly. When extreme abuses occur, the instinct is to rely on appellate courts and private remedies that align liability with identifiable harms. The danger here is that the state’s verdict goes beyond neutral adjudication and becomes a moralizing instrument—a public confession and a punitive transfer—rather than a precise, rights-protecting remedy. If workers were harmed, the legitimate path is individualized redress through private litigation, or criminal prosecutions of identifiable perpetrators, anchored in clearly defined property and personal-rights violations. A robust system of property rights and voluntary contracts, enforced by independent courts, is the best bulwark against such abuses, because knowledge about harms and remedies is dispersed and context‑dependent. Public apologies and large punitive damages imposed by decree risk substituting state coercion for rightful restitution and market-based accountability, which Hayek would view as dangerous channeling of information and incentives.

Nozickian frame (minimal state, rights as side-constraints, anti‑patterned distribution) Nozick would insist that the only legitimate function of the state is to protect individuals from aggression and to enforce contracts. If individuals directly violated rights, they should be punished or compensationally redressed. However, the justification for a sweeping corporate liability plus a forced “apology” to society as a form of collective sanction stretches beyond a rights‑protecting function. The state should not condition corporate existence or compel public contrition as a blanket moral reallocation of wealth or social status. Victims deserve redress, ideally through voluntary or privately organized settlements or criminal prosecution of the specific wrongdoers, not through a state-imposed transfer that can resemble punitive redistribution. And if damages are warranted, they should flow to identifiable victims via private claims, not as a government-controlled apology or a public-relations reckoning.

Randian frame (moral primacy of the individual, suspicion of collectivism and state paternalism) From Rand’s perspective, the core evil would be a coercive, collectivist impulse to punish or shame a corporate entity on behalf of “society.” The rights of individuals—workers who were allegedly coerced or harmed—should be defended through their own voluntary actions and private litigation against the specific wrongdoers, not through state-sponsored penance on behalf of a corporation. A public apology enforced by the state is not a legitimate moral or legal remedy; it is an intrusion into property rights and speech, and it substitutes social coercion for moral judgment. The proper response is to uphold individual rights, pursue private redress against identifiable violators within the framework of contract and tort law, and let social accountability emerge through market signals—consumers, investors, and private NGOs—without expansion of state power or moralistic state demands.

Bottom line: the libertarian view treats egregious abuses as serious rights violations requiring precise, private redress, criminal accountability for the specific wrongdoers, and a minimal state that protects property and contracts rather than issuing public apologies or using punitive wealth transfers to signal moralizing. The temptation to weaponize a court verdict as a public reckoning against a company is precisely why a libertarian order prefers private, voluntary, rights-based remedies over state-directed atonement and redistribution.