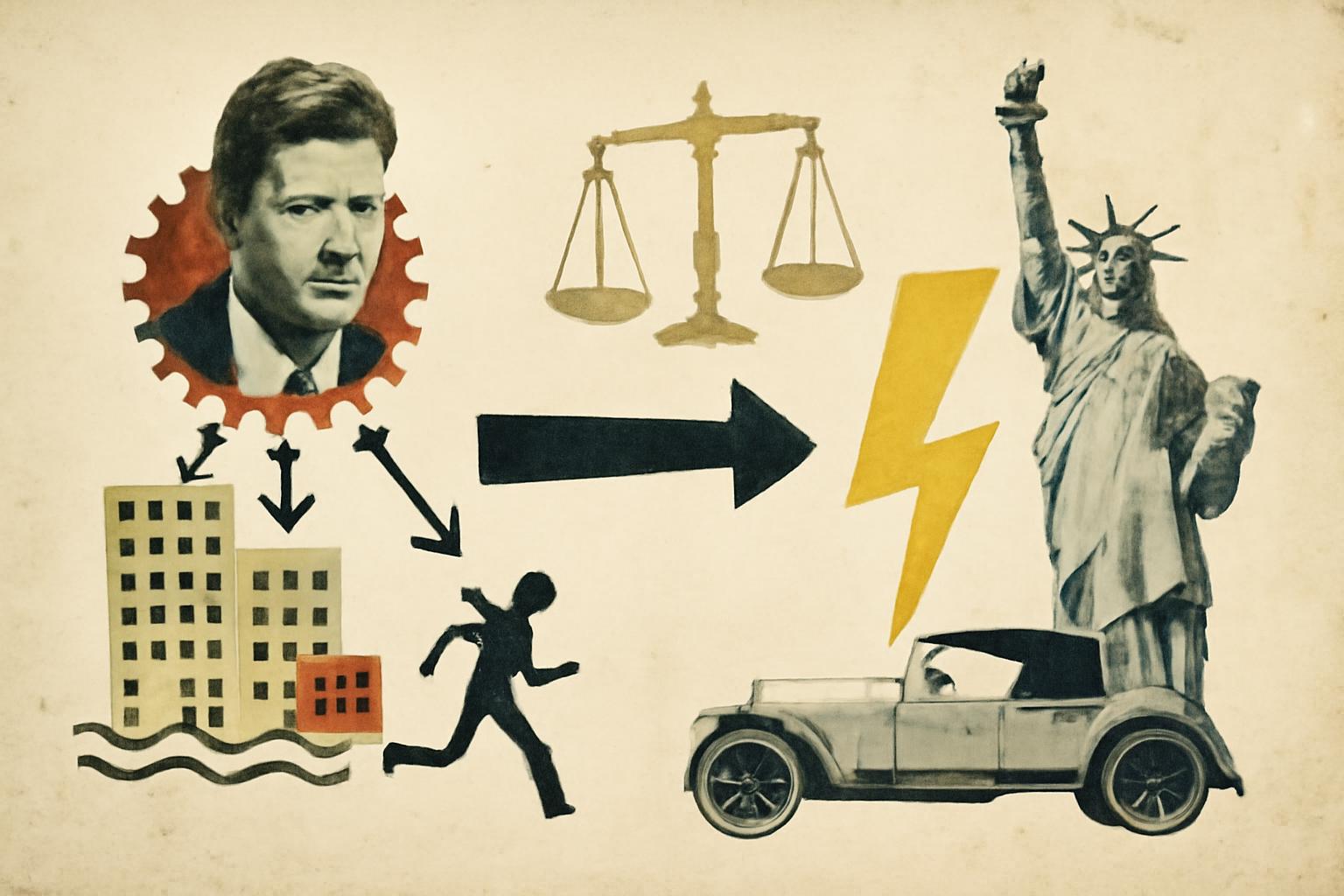

Habeck is stepping back from politics, ending his Bundestag tenure on September 1 after a career that vaulted him from Schleswig-Holstein’s environmental ministry to the federal stage as Greens co-chair. He steered through an energy crisis with cautious compromises—keeping some nuclear plants alive while continuing the coal phase-out—and presided over policies like the heating law, which sought climate targets but punished no one but taxpayers and homeowners with costly mandates. His dissatisfaction with the post-2021 trajectory, the 2023 law’s unpopularity, and the 2025 electoral setback culminated in a decision to close doors for new ones to open, with talk of future roles at think tanks abroad. In short, a man who aimed to reinvent the economy via green transformation acknowledges the limits of centralized, politically driven reform and signals a move toward quieter intellectual work.

From a libertarian vantage point, this arc exposes the creeping habit of the state to “solve” complex problems with top-down mandates rather than through voluntary, market-based processes. Hayek would remind us that energy systems and economic transitions are diffuse, knowledge-problem riddled creatures. Central planners cannot possess or coordinate the dispersed information held by households, firms, and local innovators. The so-called pragmatic compromises—extending some nuclear life, continuing coal, regulating heating—aren’t neutral; they are the state's attempt to pick winners and steer outcomes. Prices, competition, and property rights are the only institutions capable of harnessing dispersed knowledge. The longer the state tries to direct the transition, the greater the risk of misallocation, crony interference, and unintended consequences that look like progress only because they’re labeled as such by politics.

Nozick would frame the episode in terms of rights and the minimal state. The energy mandates, retrofit requirements, and tax-financed subsidies are coercive intrusions into private property and freedom of contract. If the state exists only to protect rights, then the coercive tools used to impose a “green standard”—and to punish noncompliance or delay—are a usurpation of individuals’ sovereignty over their own property and resources. The more policy is driven by moralizing goals or electoral calculations, the more it drifts from a rights-respecting framework into a redistributive, coercive enterprise. Habeck’s retreat from a central plan toward institutions that respect voluntary exchange would align with Nozick’s vision: shrink the zone where the state shapes energy choices and expand the arena where individuals can decide how to heat, power, and light their lives through free association and private arrangements.

Rand would insist that government’s proper role is protecting individual rights, not engineering a preferred energy future through coercion. The climate crusade, when forced through regulations and mandates, becomes a redistribution of wealth and a violation of rational self-interest—an assault on the moral or rational claim that each person should live by the judgment of his own mind and property. The green transformation, if pursued by command, requires coercive power that corrupts both liberty and innovation. A freer approach would unleash voluntary, market-driven innovation in energy: private investment, competitive pricing, transparent property rights over energy resources and infrastructure, and removal of subsidies and fiat mandates that distort incentives. If customers are allowed to decide, and providers compete to deliver reliable, affordable energy, then efficiency and invention will outpace any centrally declared timetable.

Practically, the libertarian path would emphasize:

- Reduce coercive mandates in housing and energy policy; repeal or sunset heavy retrofit requirements; allow homeowners to choose heating and energy solutions without bureaucratic punishment.

- Deregulate and expand competition in energy markets; privatize or liberalize grid access so private firms can innovate and coordinate supply through voluntary associations and price signals.

- Limit subsidies and state-directed “green” subsidies; shift incentives toward property-rights-based frameworks that reward efficient, innovation-driven energy solutions.

- Protect civil liberties and the right to contract; resist culture-war coercion disguised as environmental or moral progress; let communities, businesses, and individuals opt into energy solutions that reflect their values and budgets.

In this light, Habeck’s move toward distance from the Berlin milieu and a future in research institutes or universities could be seen as a retreat from the futile attempt to legislate a perfect green state and a pivot toward ideas that respect freedom, institutional learning, and the spontaneous order that Hayek prized. The only sustainable climate and energy outcome is one born from voluntary exchange, private property, and competitive experimentation—not from central planning masquerading as prudence. The state’s proper function is to protect rights, not to orchestrate an alleged green utopia; beyond that, freedom, responsibility, and market competition will do the rest.