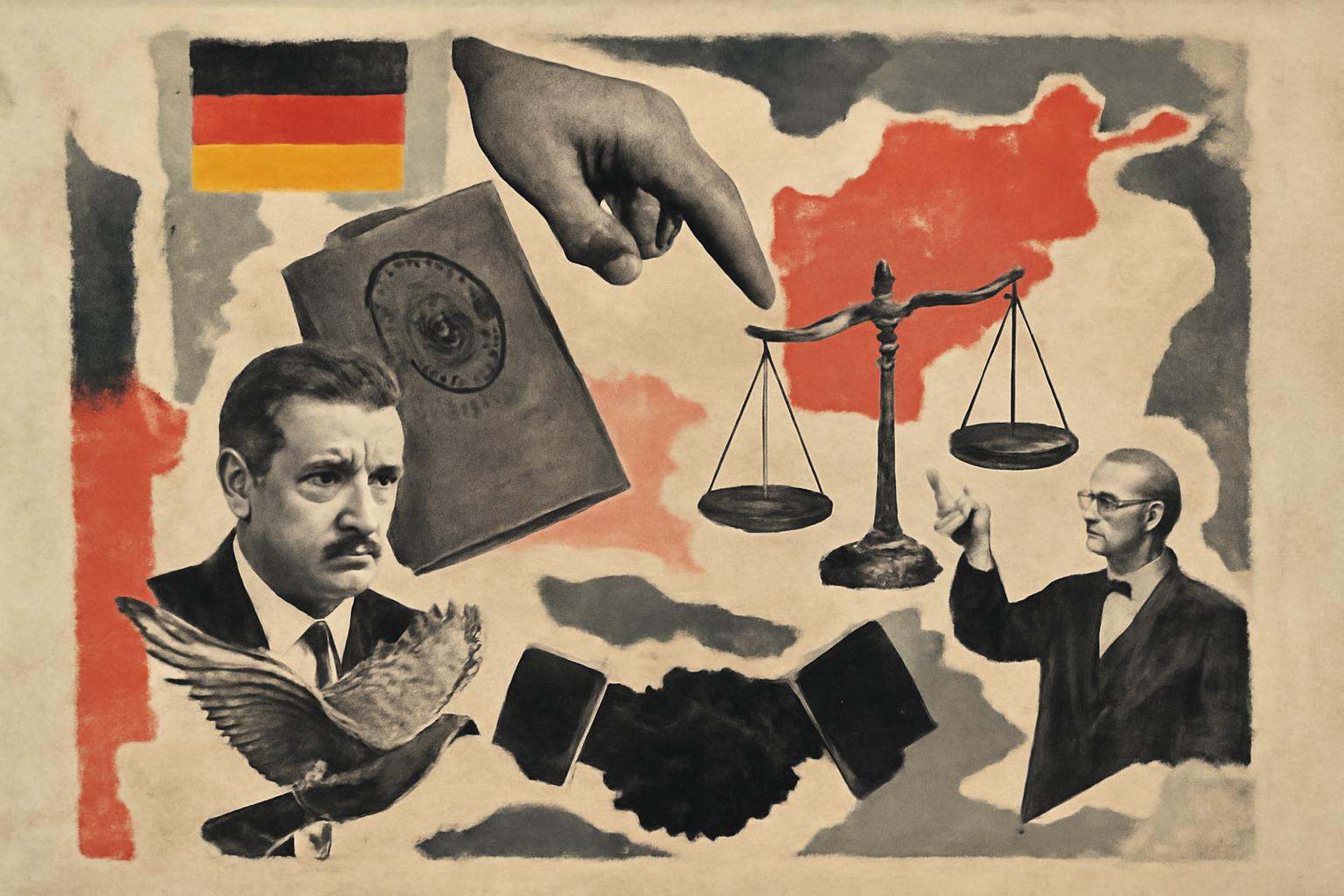

German authorities missed a series of deadlines to issue entry visas to Afghans who had been promised admission under a state program, triggering court warnings about coercive fines and highlighting a habit of reactive, emergency rulings rather than principled policy. By mid-June 2025 thousands remained in Pakistan despite promises, with opaque government explanations and ongoing legal battles over visa issuance. A recent court decision granting visas to a professor and her relatives was appealed away, and later actions signaled a relaxation of entry restrictions for at least one Afghan family, only to see further deportations and detentions among those with promises. By August, thousands more Afghans with admission promises were still in Pakistan or being deported between Pakistan and Afghanistan, while Afghan local staff who were supposed to be protected remained in limbo four years after the Taliban’s rise. The pattern is one of bureaucratic coercion masquerading as humanitarian policy, with promises made, but enforcement inconsistently applied and backed by coercive pressure rather than principled rights-protection.

From a libertarian vantage point, this exposes the core fault of a state that pretends to manage human need through central planning and coercive apparatus rather than through voluntary, rights-respecting means.

Hayek on the rule of law and spontaneous order: The problem is not only delays but the systemic reliance on discrete, discretionary interventions, emergency injunctions, and punitive fines to compel outcomes. Law must be general, known, and predictable; when the state treats immigration decisions as ad hoc commands backed by fines, it undermines the very trust in rules that enables people to plan their lives. The coercive fine mechanism is a symptom of centralized manipulation rather than a neutral, rules-based system. A libertarian view would insist that immigration policy be narrowed to protect basic rights, with any ongoing obligations judged against general principles rather than ad hoc political windfalls. The failure to honor promises reveals how a large, interventionist state distorts the spontaneous order of voluntary human cooperation that would otherwise meet humanitarian needs more efficiently through private, reputational networks, charity, and market-based sponsorship.

Nozick on rights, borders, and the minimal state: The proper function of government is to protect individual rights, not to manufacture, fund, or coerce humanitarian outcomes. If a promise was made by a political entity, that promise exists within a framework of coercive power; honoring it is not a moral entitlement of foreigners but a matter of how the state conducts its own operations. Yet the state’s resort to coercive fines and forced migrations reveals that it cannot be trusted to handle such promises consistently. A minimal state would not preside over a web of cross-border obligations funded by taxes used to compel entries or deportations; it would either allow voluntary sponsorship and private arrangements or shrink to protecting property rights and contract enforcement, leaving humanitarian acts to voluntary charity and civil society rather than state machinery. The repeated use of coercion to manage admissions shows the incompatibility of such programs with a rights-respecting order.

Rand on individual rights, property, and voluntary action: The humanitarian impulse embodied by a state program is morally suspect when funded by coercive taxation and enforced through detentions or deportations. People are ends in themselves, and the proper moral action is not to deploy the coercive apparatus of the state to “solve” humanitarian crises, but to respect individual rights and rely on voluntary, voluntary-compensation-based acts of charity, sponsorship, and market-driven solutions. The migration process should be a matter of voluntary exchange and private responsibility, not a bureaucratic distribution of favored outcomes backed by fines or deportations. The failures here illustrate the moral hazards of a statist approach: it uses coercion, secrecy, and legal maneuvering to appear “compassionate” while undermining trust, property rights, and peaceful, voluntary cooperation. A Randian stance would call to shrink or abolish the centralized program, restore voluntary associations, and reduce the state’s power to coerce individuals into subsidizing or enforcing admissions.

Practical libertarian implications and remedies would emphasize: - Abolishing or sharply constraining coercive immigration coercion, fines, and the state-directed administration of asylum promises. - Replacing centralized admission schemes with minimal-state protections for rights and leaving humanitarian sponsorship to voluntary private actors, NGOs, and market-based networks that operate transparently and without coercive tax funding. - Expanding voluntary sponsorship models and private contracts that respect property rights and freedom of association, rather than relying on a top-down bureaucratic system that produces delay, opacity, and punitive measures. - Recognizing that true humanitarianism arises from voluntary human action, not from a state monopoly that claims to “solve” needs by coercing others to fund and enforce admissions.

In short, the episode demonstrates how a big, interventionist state corrupts the moral impulse behind migration aid into a herding of people through legalistic coercion. The libertarian remedy is to roll back state power, honor rights by protecting them rather than weaponizing them against those seeking admission, and entrust humanitarian outcomes to voluntary, rule-bound, market-compatible means consistent with Hayek, Nozick, and Rand.