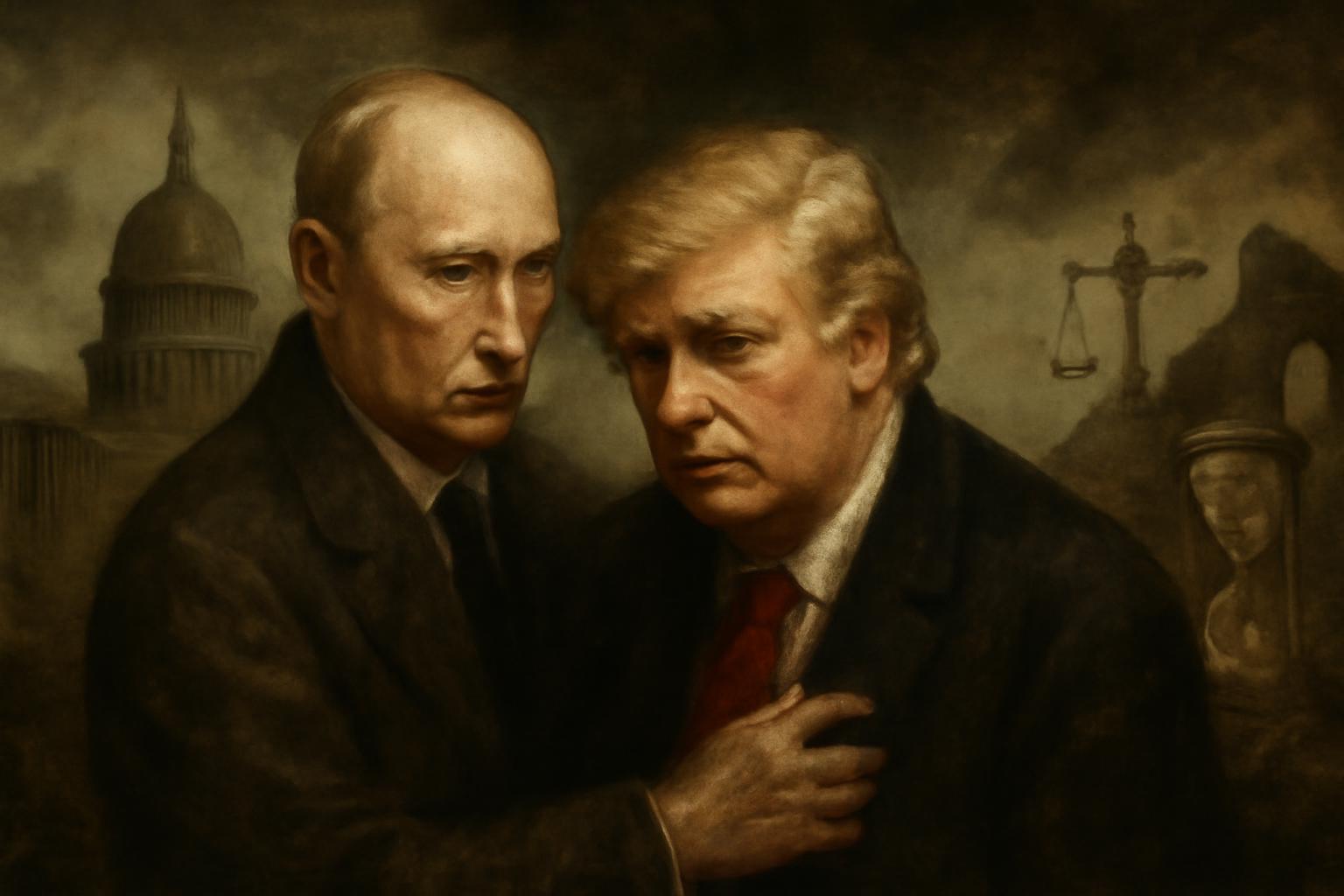

Under the cold glare of a frozen theatre, the Alaska encounter unfolds not as triumph but as a fracture in the optic of power. The veteran observer—a silhouette against the map-drawn dusk—measures the scene with the scalpel of memory and declares that Washington stood ill-prepared, a city on the edge of a thawing lake, while Putin, patient as a classical trickster, managed to draw Trump into his orbit, not by force, but by the gravity of perception. The pretense of a ceasefire without preconditions dissolves into a retort that the stage is merely set for grander gambits; Putin gains the spotlight, a psychological win that makes Trump assent in rhetoric, at least for the moment, to consult Zelensky. The old quarrel of lands and borders shifts its weight, and the world—like a chorus in a tragedy—feels the tremor before the fall.

For Ukraine and for the security architecture of Europe, the consequence is not relief but foreboding. Putin’s post-summit whisper—that “Trump and I have agreed”—and the caution not to torpedo the arrangement suggest that the line between alliance and illusion has grown perilously thin. If Trump has thus become, in verbal form, a line of Moscow’s thought, then the republics that depend on Europe’s balance find themselves adrift in a sea where the compass points to raw interests rather than shared destiny. The talks suffered from weak preparation, and the envoy, Steve Witkoff, appears not as navigator but as a pawn moved by hands unseen—hands that tilt the map toward a symmetrical dance of power rather than a concert of liberty. Trump’s Fox News reflections on rare earths, oil, and gas underscore a preference for the inexorable arithmetic of commodities over the patient labor of diplomacy. The psychology of coercive bargaining returns, as if from a nineteenth-century cabinet of curiosities, to remind us that the present can borrow its charisma from antiquity only to hollow out the future.

Von Fritsch’s critique lands like a cold blade: Trump’s posture mirrors a heedless century’s appetite for strength, a caricature of power politics that mistakes the strength of a nation for the weakness of its interlocutor. It is not a misreading of the other so much as a misreading of the theater in which we all perform; the person with whom one negotiates is not merely a negotiable object but a history—complex, opaque, potentially fatal to one’s own sense of self. The pattern he sees is not novel in its surface, but ruinous in its implications: a political temperament that gilds crude advantage with the rhetoric of problem-solving while failing to grasp whom it addresses, or what it costs those who stand beyond the dais.

A Moscow visit hovers on the edge of possibility, yet remains uncertain, as if the next act depends on weather more than will. ARD notes the absence of concrete results, and the mind, trained on the Greek tragedy of fate, recalls that vigils before a catastrophe are often longer than the catastrophe itself. In such moments, the modern ward of history—its journalists, its commentators, its flaring tweets—begins to resemble the actors in a Euripidean chorus: aware of the ruin to come, yet powerless to alter the syllogism that binds them.

And so we return, with the gravity of a waning culture, to a larger ruin: the sense that Western civilization is slipping from its own grand narrative, a decline narrated in the key signatures of power rather than in the ethics of inquiry. Nietzsche’s memory hums in the air—the will to power, the transvaluation of values, the hazard of looking for meaning in the cold arithmetic of advantage. The Greeks would call this a tragedy of omens: a people who believed themselves masters of fate discovering that their craft, when untethered from restraint, becomes the instrument of their own eclipse. In the theater of international affairs, the curtain may rise again, but the stage remains the same weary marble where ambition, distrust, and calculable risk enact the same grim drama, time after time.

I lament not only the particulars but the mood that allows such scenes to pass as policy. If Western civilization is to endure, it must learn anew the old art of restraint, the patient discipline of dialogue, and the stubborn fidelity to a horizon larger than one’s own power. Without that, we are condemned to watch the same miscalculations replay themselves—each act a slight against the possibility of wisdom, each exit a step away from the chorus of shared humanity. To borrow from tragedy and philosophy alike, we stand at a crossroads where the will to power masquerades as governance, and the only remedy is the quiet refusal to be enthralled by the spectacle of strength when it erodes the very ground on which civilization stands.