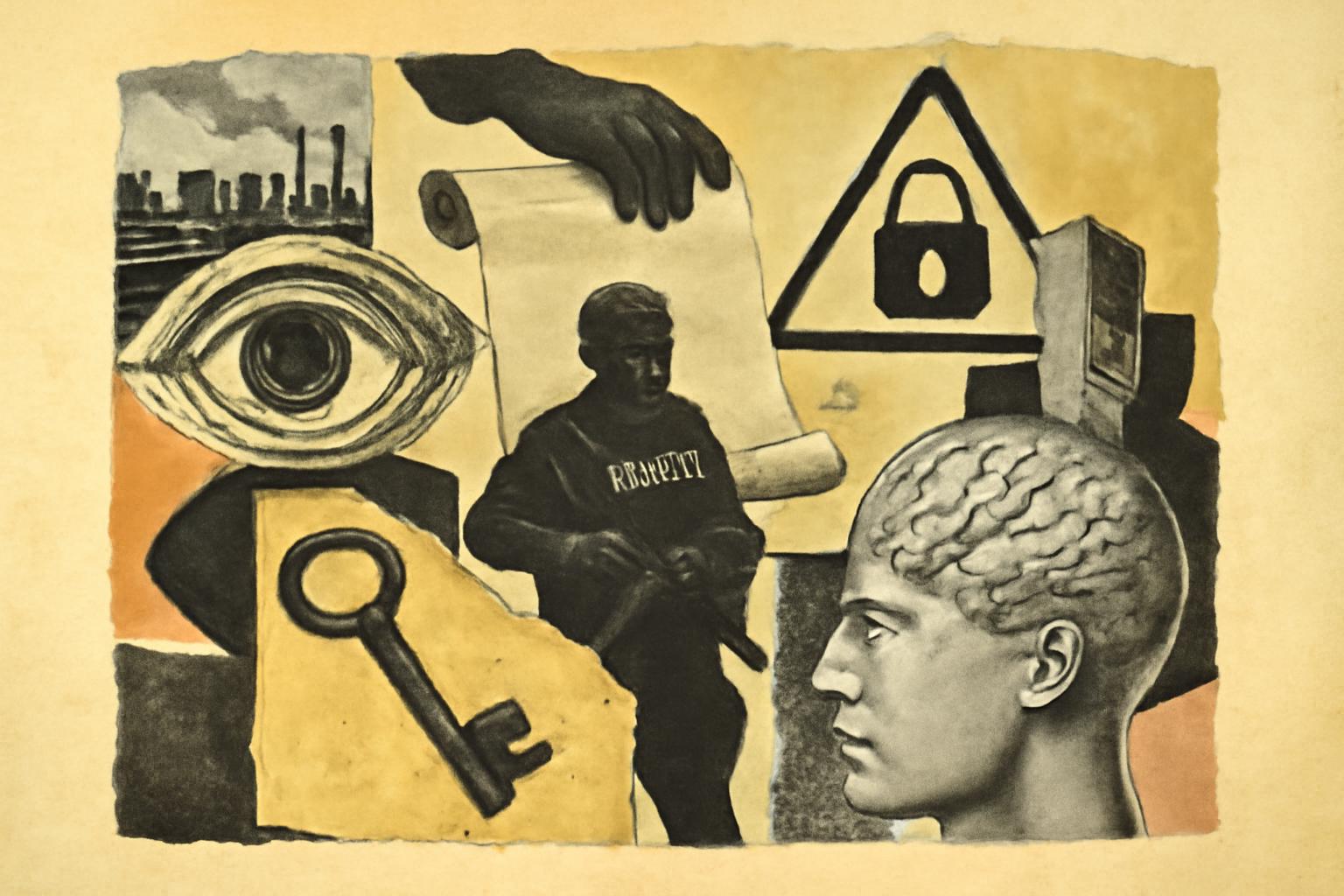

a state that robs a private home of its contents in the name of national security is showing what it believes its own legitimacy rests on: coercive power over information, over property, over thought itself. the claim that “no one is above the law” rings hollow when the same apparatus that makes such claims can orbit around a person’s private papers, a person’s history, a person’s very mind and the channels through which ideas move. the raid is not about truth-seeking; it is about intimidation, about signaling that the state will enforce its secrets with the same zeal it pretends to apply to justice.

hayek was right to warn that knowledge resides in dispersed, private actors, not in a central office with a warrant pad and a press secretary. the knowledge problem means you cannot design a perfect system from the top, especially one that can distinguish between legitimate national-security concerns and the kind of bureaucratic ambitions that mistake panic for prudence. centralizing the decision to rummage through a citizen’s private correspondences invites misallocation of resources, grave errors, and the normalization of coercive curiosity. even the best-intentioned officials are embedded in a system that rewards power, not truth.

nozick would insist that the minimal state exists to protect rights, not to expand its reach by redefining what counts as consent, property, or evidence. if a home can be invaded in the name of classification regimes or leaks, then the state has crossed from protecting rights into arbitrating what the right to information should look like. the claim that force toward information is compelled by a higher good can be used to justify almost any extension of coercion, provided it wears the cloak of “national security.” but a government that pretends to serve liberty while it trims the liberties of private individuals is a government that has forgotten the essential purpose of rights: to prevent others from coercing you, not to coerce you in their behalf.

rand would ask whether the operation respects the sovereign rights of the individual—the right to think, to own one’s own thoughts and communications, to control one’s own property. if the state’s apparatus treats classified materials or alleged leaks as a license to invade private life, it reveals a worldview where individuals are objects to be managed for the collective, not agents with minds to be guided by reason. a legitimate government is a protector of rights, not a collector of secrets or a ceremonial executor of political will. when force is claimed in the name of “the law,” yet undermines the very boundaries that give law its moral authority, the result is not safety but a precendent: the state can decide who may possess information, and when, and for what reasons.

the lessons for libertarians are sharp and simple. shrink the space in which such intrusions become thinkable. restore the primacy of due process, require warrants based on concrete, perspicuous evidence, and apply the fourth amendment with unwavering consistency, not as a convenient veil when convenient political actors are involved. reject any rhetoric that elevates secrecy above accountability, that treats a private person’s documents as fungible evidence in a political game rather than as the inviolable property of a mind and a private life. end blanket classifications as a license for coercion; demand that any intrusion be justified by narrowly tailored, narrowly supervised processes with independent review and sunset provisions.

the state’s reflex to raid is not a sign of strength but a symptom of dependence on force to mask its own incompetence to govern through persuasion and principles. if liberty is to endure, it must be defended not by slogans about law but by a relentless commitment to the rules that make law legitimate: protection of rights, restraint of aggression, and accountability that begins with the recognition that the government itself is not exempt from scrutiny. the only viable antidote is to reawaken a politics of individual rights, limited government, and voluntary exchange—where information flows freely under the protection of property and contract, and where no one assumes they can override another’s mind or private life in the name of security.